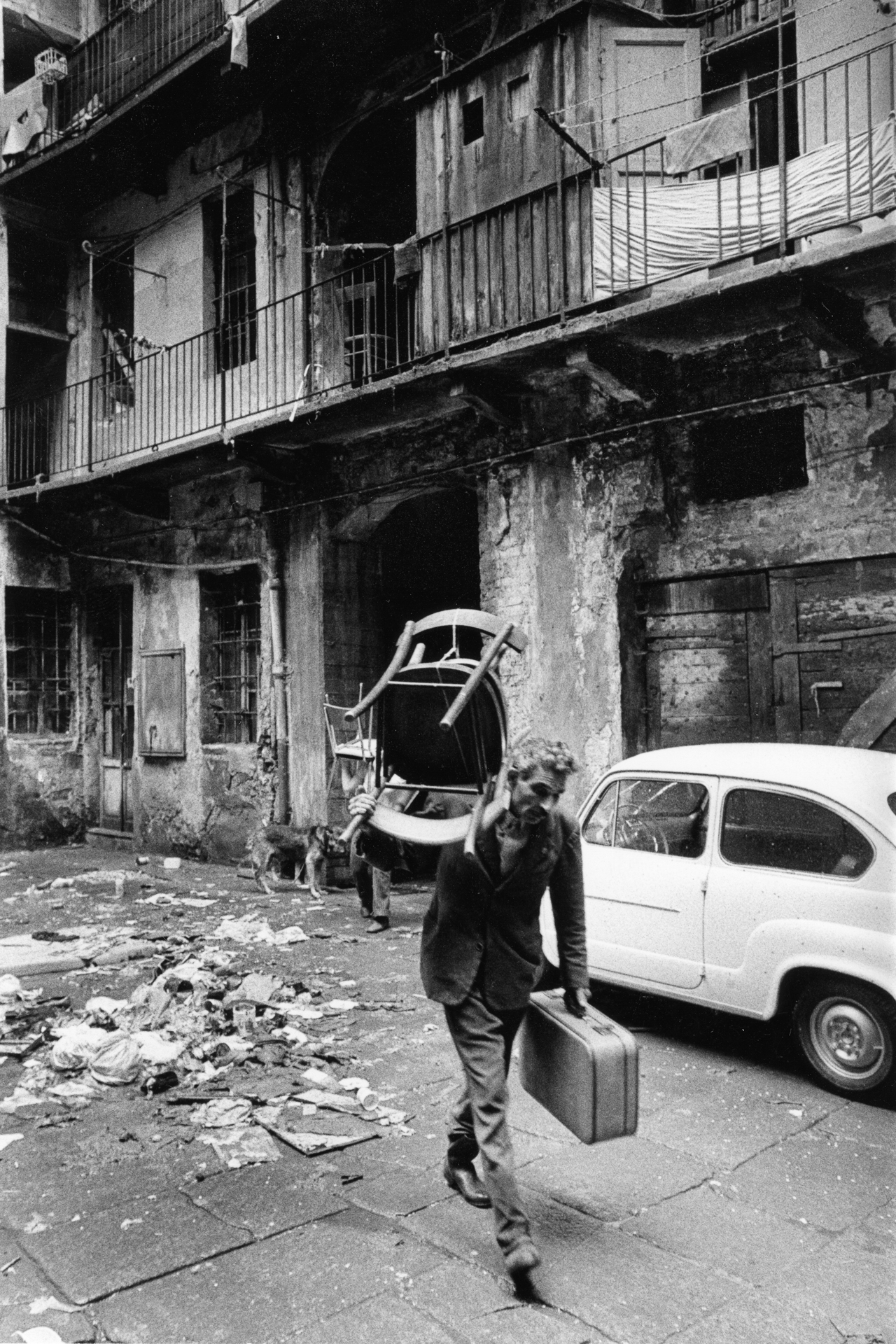

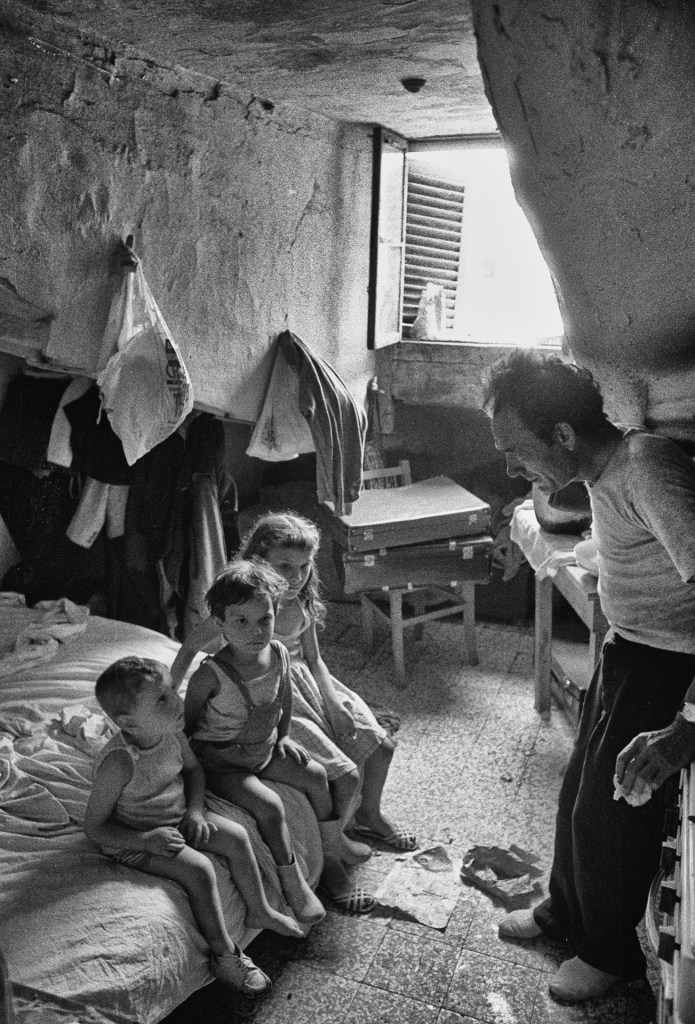

At the beginning of the 1970s, Italy experienced a new wave of migration, both internal and abroad, driven by the search for work in the major factories and industrial districts of Europe. From the South, thousands of young people moved to Turin, attracted by FIAT’s hiring campaigns: for many, integration was difficult, marked by dilapidated attics and hastily built ghetto neighborhoods around the factories.

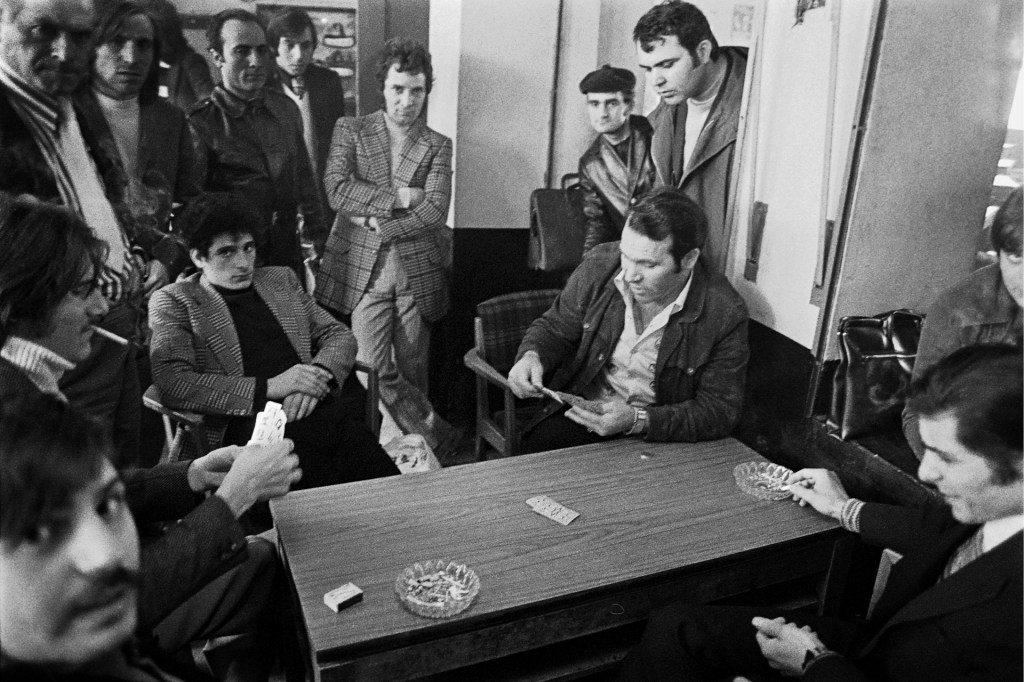

Across the border, West Germany became a favored destination. In Wolfsburg, Volkswagen brought in hundreds of Italian immigrants by train, housing them in workers’ villages separated from the city. Even harsher was the condition of those employed by the Federal Railways, forced to live in the Bauzug—trains converted into kitchens and dormitories, constantly on the move and without a permanent home.

In Belgium, coal mining continued to attract migrants. The work remained heavy and plagued by serious occupational diseases, but the new arrivals—young Sicilians, Calabrians, and Sardinians with stronger educational backgrounds—fueled union struggles and contributed to improving living and working conditions.